News

Penelope’s Trip to California

01.21.2016

Penelope spent the past month in California, visiting numerous galleries, museums and artists’ studios. Two people in particular I would like to share with our readers are Meghann Riepenhoff in San Francisco and Steven DePinto in Santa Barbara.

Meghann, who is represented by Monique Deschaines, is an established contemporary artist who is presently working with cameraless images. She was recently featured in the San Francisco Chronicle, which can be seen online at sfgate.com. Her work is very exciting, unlike anything I have seen. Below are a few of her images and a short write up on her work.

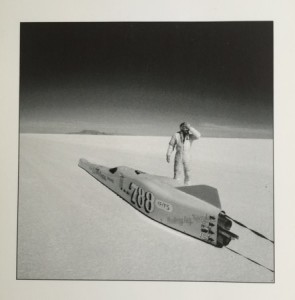

Steven is currently showing at Gallerie Silo in Santa Barbara. The work on view is from the 1970s through 1990s and was taken in the desert. Although I found the race car photographs interesting, it was the found objects, very much like Penn’s cigarette butts, that I found the most intriguing. Below are a few images and a short write up on his work.

And, of course, no visit to California is complete without a stop at the Getty where I had a delightful lunch with Virginia Heckert and Frances Terpak.

Meghann Riepenhoff

Littoral/Litera

By Sarah M. Mill

What is a literal land erscape? When I interviewed Meghann Riepenhoff about Littoral Drift, she said: “The impetus for this series was to make a literal image of the landscape, in the face of a human situation where photographs often replace experience. I wanted to engage the actual and make the most hyper-literal photographic representation of the landscape I could…” Her words present an intriguing problem: landscape, in common parlance, is the place we live or the territory we move through. But in the history of art, landscape is a symbolic construction—nature or environment shaped into a culturally coded picture, never nature itself. Unlike most photographs, which are mistakenly termed indexical, Riepenhoff’s cyanotypes are true indices: nature’s elements impress the papers and make their own marks. But index and landscape should be opposites; nature cannot code its own image. In landscape, it’s the human shaping that renders a meaningful picture. So how can there exist a literal littoral landscape? Who is its maker? How does it mean?

Experience: it’s the third element at play in Riepenhoff’s program, between index and image, between nature and landscape. The works should be experience, she says, not offer a high-resolution substitute for it. “I also wanted to make work that was like the land where I was working: wild, dynamic/impermanent, tactile, messy, beautiful, unpredictable.” In both their making and their presence, the cyanotypes of Littoral Drift become a material expression—rather than a pictorial representation—of places, forces, flux. Experience mediates: this is how one arrives at the literal landscape. Landscape-as-picture is so deeply embedded in the psyche that it becomes embedded in the body, too, and in the body’s gestures. In these littoral works, Riepenhoff acts less as a pictorial translator than a mediating body, filtering the powers of nature through corporeal and intellectual memory.

Cyanotype has two chemical components. When Riepenhoff prepares her papers, she often coats the lower half of a rectangular sheet with only one component, then flips it around to coat the other half with the second. Where the two meet to combine in a typically “complete” formula: a horizon line. In Western landscape, horizon is the only essential element, the origin of meaning; articulation of the horizon sets interpretation in motion. Here, the horizon invented from a simple chemical meeting zone transforms index into abstraction and unleashes metaphor, turning the smack of salt water into something we can see as ocean waves, streaked skies, golden dunes, distant hills, skidding clouds, lashes of sunlight.

And what of the works where paper is completely coated in cyanotype, both chemicals combined for the classic deep blue ground? These eschew the imaginary horizon, yet they create and release pictures nonetheless. Standing in the ocean to dip these massive papers, Riepenhoff and her assistants manipulate (but never fully control) the depth, the angle, the timing, the sediment deposits, the encounter to encourage the water to hit the paper in the image of a wave, or an eddy, or an effervescent underwater view. Her body, with its image-memories, is the lens, and when you perceive a picture you become the frame. We discern, in the literal, littoral index, a ghostly echo of the pictorial landscapes already given us, millions of times, through the lens.

In the 19th century cameras and lenses were designed to produce photographs that imitated older paintings within the traditions of Western art—images that would be understood as intelligent landscapes rather than the chaos of unmediated nature. The camera has never given us nature itself. What Riepenhoff’s Littoral Drift reveals is that the other technology attendant at photography’s birth the cameraless photogram in which objects leave their own silhouettes on sensitized paper—has always contained the seeds of another kind of landscape. Now—when lens-made pictures exhaust our minds but our bodies still carry them as unconscious law, seeing them everywhere— Riepenhoff’s wild cyanotypes precipitate a new alchemy of the sublime.

Meghann Riepenhoff, Littoral Drift Nearshore #209 (Springridge Road, Bainbridge Island, WA 02.12.2015, Fletcher Bay Water Poured and Fletcher Bay and Fay Bainbridge Silt Scattered), grid of unique cyanotypes, each 19 x 24 inches, totaling 114 x 216 inches.

Meghann Riepenhoff, Littoral Drift Nearshore #215, (Springridge Road, Bainbridge Island, WA 03.19.2015, Rainstorm, One Hour and Forty-seven Minutes), unique cyanotype, 144 x 42 inches

Steve DePinto

For three decades Steven De Pinto has explored the esoteric and abandoned deserts of Western America. From his fascination with land-speed racing culture, aerospace technology, and the detritus of desert-used weaponry, he has produced a body of photographic artwork that has achieved international recognition.

Using historical maps from the 1800s to track forbidden routes and lost sites, DePinto’s purpose in the desert has been as much about integrity as fascination. His images honor their subjects both from his mechanical knowledge, and from the construction of his photographs. He knows about aerospace, engines, racers. He builds his own cameras, including a pinhole 4×5. To him, each camera has its sensibility, personality and look. He believes the desert racers who ply their speed-dreams in anonymity are every bit the artists he tries to be.